Why do we need art?

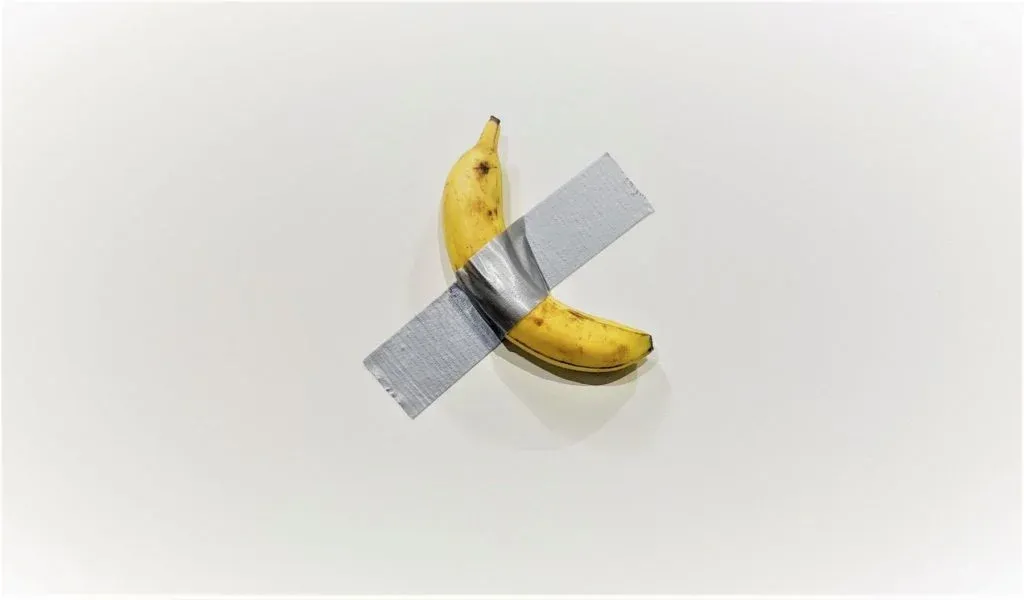

The recent sale of Maurizio Cattelan’s duct-taped banana and subsequent eating of the latter caused a fresh wave of contemplation on what art is and why it is.

Symptomatically, the comments and discussions weren’t very heated. The banana, its young owner and its outrageous cryptocurrency-fuelled $6.2 million price tag were noted with tired frustration. What was supposed to be a provocation fell short on all fronts. The sale followed another discussion in the increasingly narrowing art circles about “The birds” - ballooned penguins priced between €40,000 and €60,000 at London Frieze. The gallery representing the ‘artwork’ stated that “the work offers a reflection on how we all take part in a larger global system of distribution”. Neither the explanation nor the work of art itself offered much meaning, let alone promised any impact on the state of penguins or the system of distribution.

The art world moves further and further into the realm of a senseless, unnecessary and detached reality, where every communication is a loud manifest, a weird and obscure sign leading to seemingly nowhere. When everything is a provocation the sign becomes so banal and unattractive that no one is hooked and curious enough to explore what that sign was supposed to lead to. No one really wants to see beyond it. Art becomes the epitome of a provocative, decorative and shallow life covered by the veil of fake intellectualism and unimportant names.

It isn’t a secret that in the 20th century, surrealism, dadaism, conceptualism and many other “isms” had a huge influence on the perception of what art is. In the spirit of time, art became revolutionary, manifesting, denying, suspicious, godless, excruciating, aggressive, provocative, irrational and non-sensical. Those movements made art abstract and conceptual, glorifying the mind and its secrets to the point when the lines between art and any other man-made activity became very blurred. Fountain, a readymade object presented by Marcel Duchamp in 1917, was selected in 2004 as "the most influential artwork of the 20th century" by 500 renowned artists and historians. Being a prominent member of the Dadaism movement, the author himself stated the purpose of the Fountain is in “everyday objects [being] raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist's act of choice”.

So what is celebrated in such an artwork? What is its purpose?

If it is an everyday object that is celebrated, then why do we need the artist? Craftsmen or machines who created those everyday objects should be given all the admiration. After all, they did create a great shape for that urinal, covered in a non-trivial festive white enamel colour; an object of ultimate utility and restraint. Or do we celebrate the dignity of everyday material existence? The act of creation and being in this world as opposed to nothingness? Then God should be the one to praise. Or is it perhaps the act of artist’s choice that is the purpose? Courage to decide to pay such particular attention to such a non-particular object? A desire to express and to say something, no matter how profane or pathetic? To make an aesthetic judgement and a statement?

It seems that the artist figure in the 20th century went through a period of great deconstruction, completing the cycle, which was started in the Renaissance, coming to its opposite end. During the times of Leonardo and Botticelli, the ideal was to become a polymath, a master of various crafts and arts, to be as well-rounded a man as possible and to develop as many talents as the time will allow. The purpose was to synthesise, to be a virtuoso - a man of great virtues, which included both intellectual and physical skills and knowledge. A Renaissance man was someone of artistic excellence and outstanding taste. Whether a ruler, a warrior, a philosopher or an artist, one had to acquire the main virtues of applied knowledge and common taste. Yet 500 years have past, and the infamous “alienation from the product of labour” created a very different type of ideal: highly specialised, individualised and conceptual. The ideal man is guided by their desires and dreams, unstructured and undifferentiated, individualistic and thus increasingly cryptic and impossible to be perceived directly. The product of such an ideal man comes from his head and mind directly, from the depth of his imagination. The more distressed and conceptualised one is, the better.

The change of the ideal led to the change of the figure of the artists, who instead of mastering the art of synthesis through his individual corporeality, became the master of intellectual analysis. The mind became the idol, the search for meaning - the ultimate goal.

But what if the real purpose of the art is to serve as a mirror? What does duct-taped banana tell us about ourselves? And more importantly, what does our view on the duct-taped banana tell us about ourselves? Have we finally castrated our masculinity? Or did we sacralise the basics of comfort (food), making it an idol? Or did we just lose the connection to our senses in the process of chasing the concepts and meaning?

The conceptualisation of art is a symbol of our detachment from our material reality. A symbol of de-sacralisation of the body, its senses and feelings. The absence of figurative art and omnipresence of expressionism is the absence of faces, of humanity, giving in to dry intelligence (artificial or otherwise).

If art is a mirror, it must have a dualistic nature, to be fully formed from the material yet have an immaterial origin - an idea. Just like the immaculate conception, an artwork has to be a combination of corporeal and ideal. And this is why real art possesses power, which is very different to the power of nature, which is not man-made. Art is human. The desire for art comes from the belief in the dignity, talent and virtuosity of Man. Man in all its corporeality and idealism.

Art doesn’t have to soothe, entertain, or delight, it should show our state at any particular moment. To serve its purpose of mirroring the Man fully with all his virtues and vices, art should be a synthesis of the great mastery of the matter (the form), the courage of the free and open will and a refined judgement (the content). And each true artist, as well as a man of excellent artistic taste, should possess the art of the matter, the art of the will and the art of the judgement. Only then can we use art to check what has become of us and what we are cherishing and celebrating. What are our true desires?

If we are tired of looking at everyday objects stuck to the wall or frustrated by the lines of Amazon-ordered ballooned penguins it is a very promising sign of the change of our desires and aspirations. Our frustration and indifference are signalling a growing desire for human mastery of colour and form; the need for more senses and sensibility in art and in ourselves. It signals a return of the ideal of a virtuous renaissance man (or woman?), masterfully combining the form and the content.