Iconic women artists of all times

Introduction

As we have joined the world earlier this month in the celebration of Women’s day, we would like to take our reflection one step further and look at the place of women in the broader art world.

This article will be divided into two parts. In this first section, we will explore the works of women artists who have used art as a catharsis to express their traumas and suffering, materializing them into sublime masterpieces. In the second section, which will be released later, we will put the spotlight on some of the great women artists who have moved the frontiers of the art world through their creations and actions.

Transforming suffering into masterpieces: art as a therapy and as a cathartic act

In this article, we are interested in both discovering or discovering the stories of some of the women artists who have profoundly marked the history of art as well as the transcendent effect that art can have on tragic, doomed-like destinies. In particular, we will take a closer look at the lives and the works of three great artists: Artemisia Gentileschi, Frida Kahlo and Yayoi Kusama.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656)

The etymology of the name “Artemisia” is derived from Latin and Ancient Greek and is associated with “Artemis”, the Greek goddess of the hunt, wilderness and childbirth. The goddess is renowned for her strength and independence, qualities that Artemisia Gentileschi - the Italian Baroque painter we will be studying in this article - upheld during her life, notwithstanding the painful and difficult life experiences she had to endure. She mastered the art of oil painting at a time when women were not allowed to study art and become artists. Her deep admiration for the Caravaggio led her to paint the vibrant and lively historical scenes intensified by her deliberate use of chiaroscuro that are characteristic of her work. Her works are in the image of her personality and life. Dramatic, bold and powerful.

Her life in brief

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome and was the daughter of the painter Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639). She learned painting from her father and met Caravaggio in his studio. There, she developed a taste for theatrical staging, dramatic lighting, and expressive gestures. Even early on, her favorite themes revolved around the depiction of women in art.

Despite her talent, Artemisia was rejected from the Roman academies because of her gender. However, her father recognized her skill and arranged for her to study with Agostino Tassi, a painter who was his friend at the time. Tragically, Tassi raped her in 1611 when she was 17 years old, leading to a long and traumatic court ruling during which she was slandered, humiliated and tortured.

To help Artemisia escape this trauma, her father arranged her marriage to Pietro Antonio Stiattesi, a Florentine painter. She moved to Florence, where she began to gain recognition with her paintings depicting strong women figures of the Antiques or from the bible, put in spotlight with strong chiaroscuro effects a la Caravaggio. She worked on commissions for princes and was admitted to the Academy of Drawing alongside Michelangelo at a time where women were not allowed to study art at the Academy.

Her marriage did not end happily, and Artemisia returned to Rome in 1621. By then, she was financially independent through her portrait commissions. She traveled to Venice and Naples, seeking larger projects, and found success in Naples working for churches.

Artemisia later joined her father in England at the court of Charles I. Afterward, she returned to Italy in the 1650s and died in Naples at the age of 60.

2 artworks by Artemisia Gentileschi

After the traumatic episode of the rape, Artemisia Gentileschi began to develop an iconography centered around feminine violence. In this painting, Artemisia portrays Judith, a character from the Old Testament known for avenging her besieged city by seducing Holofernes and later beheading him.

Stylistically, this painting exemplifies Artemisia’s singular approach : strong and powerful women from the Bible are depicted in a dramatic manner, with intense chiaroscuro effects.

In terms of meaning and impact, it is believed that Artemisia gave Holofernes the facial features of Aogosto Tassi, her rapist and painted Judith like herself. In light of this, the painting serves as a profound cathartic act, symbolizing her triumph over her aggressor and her quest for revenge.

At a time when female painters were rare and often rejected from traditional art tracks, making it challenging for Artemisia Gentileschi to access male models, she painted several self-portraits. In this particular piece, she embodies the art of painting, one of the major arts. Artemisia portrays herself as independent, confident, focused and vigorous, reflecting her determination and skill as an artist.

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954)

By now, pretty much everyone has heard or knows about Frida Kahlo, the iconic Mexican artist, renowned for her deeply personal self-portraits, in which she was never afraid to exhibit her famous unibrow and to explore universal themes such as identity, pain, and resilience. I invite you to rediscover the unique life of a woman whose life was marked by profound suffering, yet who has always chosen to live life to its full potential and in a highly free and colorful way.

Her life in brief

Magdalena Frida Carmen Kahlo Calderón Asherman known as Frida Kahlo was born in Coyoacán in Mexico, daughter of a Mexican mother and a German father. She contracted poliomyelitis at a young age, hindering the proper development of her right leg and leading her to become lame. As the other children were mocking her because of this, she upheld her style and decided to wear large, loose pants and boyish style. At the time, she was passionate about natural sciences as a kid and aspired to become a doctor.

The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) is a key event in Mexico's modern history and in understanding Kahlo’s work. Indeed, this uprising against the authoritarian regime of Porfirio Díaz transformed the country's social, economic, and political structures. One of the major consequences of the revolution was the valorization of indigenous cultures and the quest for a unified national identity. In this context, art became a powerful tool to tell the story of the Mexican people and to promote revolutionary ideals such as social justice, equality, and the emancipation of the oppressed. Through her art, Frida Kahlo played a central role in this artistic and political movement and became a spokesperson for Mexicanism.

In 1925, at the age of 18, Frida was involved in a serious bus accident, in which she was impaled by a metal bar and almost died. While she was recovering in the hospital, she started painting and her father installed a mirror above her bed so she could paint herself. During this period, she created 55 self portraits, using painting to express her suffering and as a form of catharsis.

Frida's unique style blended surrealism, realism, and strong symbolism. Her work explored themes of femininity, suffering, and identity, bringing important issues to the forefront. In life in general, she was deeply ahead of her time, often dressing like a boy, sporting a unibrow and a mustache, which she proudly featured in her paintings.

In 1929, she married Diego Riviera, an established and very famous Mexican mural painter, whom she had met a couple years back. Their marriage is often described as a tumultuous union, marked by intense passions and mutual infidelities (notably with Frida’s own sister on his side, and the communist Leon Trotsky, on her side). The passionate love affair between the two artists led to divorce and remarriage. “I've had two serious accidents in my life. One was a bus accident, the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst,” said the artist, testifying to the doomed destiny of his couple. Nevertheless, the two lovers shared a mutual tenderness and admiration.

In 1930, Diego and Frida moved to the United States, as Diego was commissioned to work on several projects in San Francisco. During this time, Frida had two miscarriages, which left a terrible mark on her, as she understood that she would never become a mother because of her disease and the bruises from the accident.

In 1939, the couple made a trip to Paris, during which Frida encountered the Surrealists and became friends with André Breton and his wife. Back in Mexico in 1943, she started teaching, encouraging her students to appreciate Mexican popular culture and folk art. When she was too ill to commute to school, her students came to her house, La Casa Azul. Because of her deteriorating health, she had to undergo subsequent operations, which brought her further to her knees as her right leg had to be amputated. She died in July 1954, leaving behind her a total of 140 paintings and a lasting print on the history of art and society as a whole.

2 artworks by Frida Kahlo

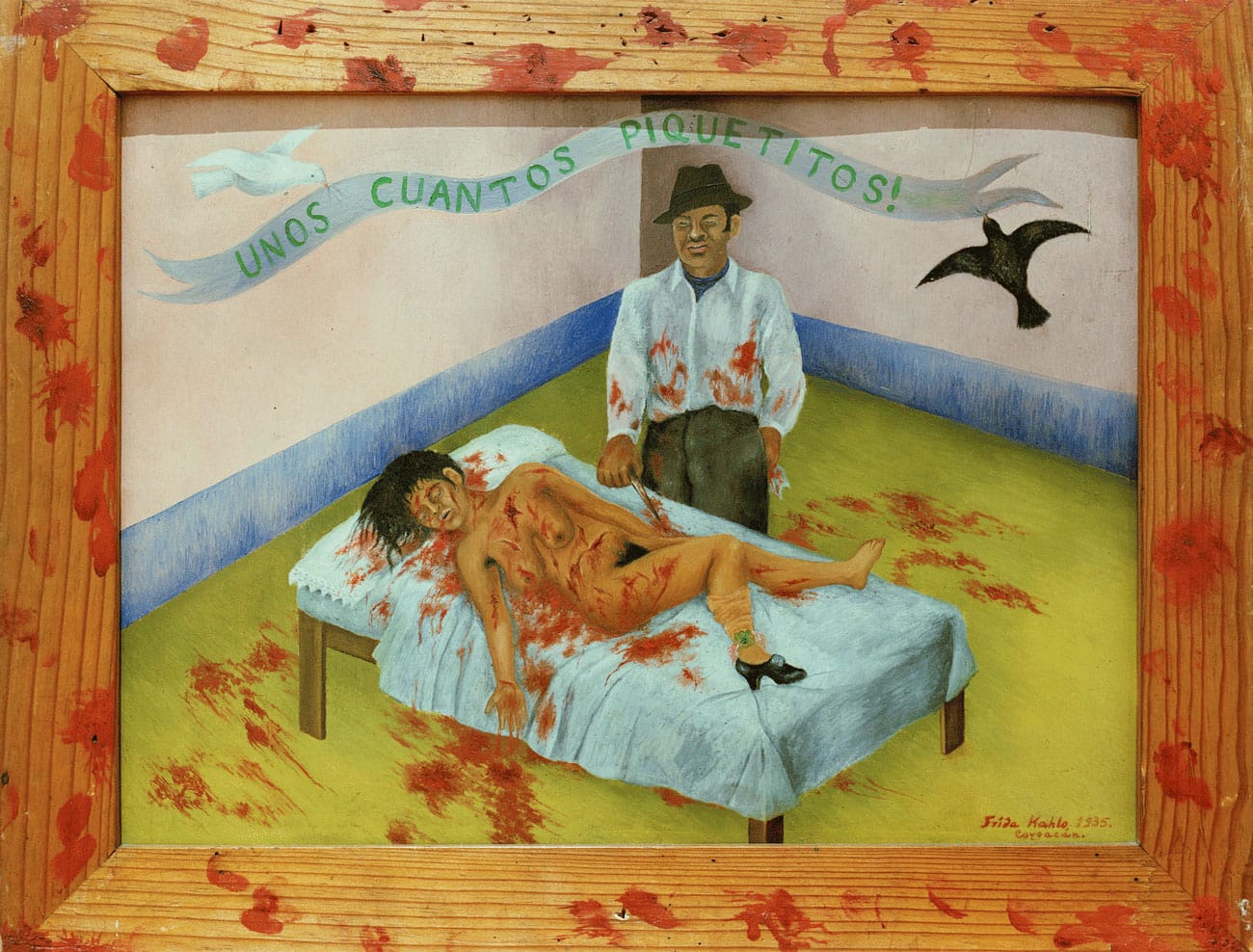

In this painting, Frida Kahlo portrays herself lying in a pool of blood, her husband Diego Rivera standing nearby, looking at her. The title of the painting, held by a dove and a raven, is ironic, as it symbolizes the numerous moral and physical wounds Frida endured during her tumultuous marriage with Diego, particularly her heartbreak following her husband’s affair with her sister.

Stylistically, the painting also exemplifies Frida’s unique approach to painting, combining the use of naïve art style with deeply realistic, almost surrealist details along with distinguishable symbols.

Among the 55 self-portraits created by the painter, this one stands out as particularly dramatic. Indeed, the artist depicts herself naked, and bound in a corset, with her spine represented by an antique column, eroded by multiple wounds. As an echo to the painful accident she underwent as she was younger, she is riddled with nails, surrounded by a desolate landscape. Standing naked before us, tears streaming down her face, Frida Kahlo portrays herself as inherently in pain and vulnerable. Yet, her expression remains, impassable, solemn and almost serene, making her profoundly resilient and powerful.

This painting is another example of Frida Kahlo’s ability to transform personal trauma into compelling visual narratives.

Yayoi Kusama (1929–present)

If you like polka dots, then you might as well like the works of Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama who was obsessed with them. Perhaps you’ve already come across or heard about her Infinity Mirror rooms that were installed in various cities of the world. In any case, this highly vibrant and colourful woman, passionate about fashion and design, already marked the history of contemporary art with her work, which blends surrealism, pop art, and psychological exploration. Suffering from hallucinations and her great fear of seeing herself disappear, swallowed up by the infinity of the universe, Yayoi Kusama decided to transcend her suffering into wide-scale immersive masterpieces.

Her life in brief

Yayoi Kusama was born in Matsumoto, Japan and grew up in a conservative family with an authoritarian father. Propelled into the realities of the Second World War, the whole family got involved in the war effort, including Yayoi who created parachutes and military clothing in a factory.

At the age of 10, she began to suffer from visual hallucinations and obsessional disorder, at which point she started drawing as a means to fight against this mental illness. Despite her parent’s disapproval, she decided to pursue art studies in Kyoto and started to exhibit her works, at a time when art was a male-dominated field in a highly conservative Japan. She anchored her work into the exploration and application of the principle of accumulation, using the polka dot as her favourite and most recurring pattern.

In 1957, Yayoi Kusama moved to the United States, with the help of the famous American painter, Georgia O’Keeffe. There, she started to work on psychedelic installations using phallic forms and organized performances in iconic places of New York, including the MoMA or the Statue of Liberty. The purpose of these happenings was not only artistic, but also political as the artist fights for several causes, including women’s sexual freedom and spiritual revolution. As she also supports women in their right to dispose of their bodies, a lot of the gatherings’ participants were naked, which caused stirs but also contributed to her notoriety and extensive media coverage.

In these performances, Yayoi Kusama rarely staged herself. She used other people’s bodies, staging them into choreography inspired by butō, a type of Japanese choreographic art, which explores the specificities of the body, in a deeply slow manner.

Having spent two decades in the United States, creating, staging, organizing and performing, the artist decided to return to Japan in 1977 and to enter a psychiatric facility, only going out to work in her studio. Being interned and working on her psychological trauma for the past forty years has given her the opportunity to develop her art as a form of therapy.

At the age of 94, the artist continues to fascinate people around the world with her psychedelic creations. She still boasts an eccentric style and an atypical and peculiar personality. Despite the obstacles posed by gender bias in the art world, Yayoi Kusama is today one of the few female artists whose work is sold on every continent.

2 works by Yayoi Kusama

In 1966, Yayoi Kusama created “Peep Show or Endless Love Show” and revisited one of the devices associated with eroticism and pornography. The experience was installed in an hexagonal space covered with mirrors reflecting a looping light device set to Beatles music. Only small-scale openings in the walls allowed visitors to view the installation, to suggest the stance of a viewer or a client engaging in voyeurism. This work preceded the artist's “Infinity Mirror Rooms”.

This work emphasizes the principle of accumulation, a pillar of her work since the 1960s. By accumulating forms, often soft ones, the artist sought to transcend her fear, presenting her work as a form of therapy. Indeed, she mentioned that this installation helped her reconnect with nature: “full of solitude, unable to sleep, I curl up in my Flower Bed for the night, because flowers are soft and loving. I'm like an insect returning to its flower for the night; the petals close over me like a mother's womb protects her unborn child”.

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944)

This is a name that had long been forgotten. This artist - who has nothing to do with Gustav Klimt - quietly revolutionized modern art and pioneered the abstract movement. Hilma af Klint painted her large-scale series The Ten Largest five years before Kandinsky created what is often credited as the first abstract works. Although, because her art was so misunderstood in her time, she asked her family to keep her work hidden for 20 years after her death.

Her art was rooted in a desire to connect with something greater, to reveal what lies beyond the visible world. With both a passion for natural sciences and deep spiritual conviction, she spent her life trying to capture the supernatural and give form to the invisible. Discover the life of a visionary woman who expanded the frontiers of modern art—far beyond the traditional and far beyond the visible.

Her life in brief

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 in Stockholm, into a family of Swedish aristocrats. As a child, she spent part of her early years at Hanmora, the family estate on the island of Adelsö in Sweden. Her parents, members of the upper class, would retreat there to escape the bustle of noble society. It was in this peaceful natural setting that Hilma developed a deep connection with the natural world — learning to observe, understand, and appreciate animals and plants.

Each Sunday, she attended church and, as she grew older, received a religious education, while also benefiting from a more progressive scientific teaching. After studying at the Technical Art School of Stockholm, she became one of the first women to be admitted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm at the age of 20.

In her early career, she painted primarily portraits and landscapes, buildings owned by her family and scenes from nearby areas. Later, she turned to botanical sketches, not just to replicate nature but to dissect and understand it. Coming from a family of seafarers and inventors, where the natural sciences were considered essential to a child’s education, Hilma inherited this scientific curiosity. She approached art with the same rigor: inventing her own visual language, symbols, and guiding lines. Her colors held meaning, and her representations of plants and animals followed internal structures — a system of pictograms that we now perceive as abstract art, but which for her represented a deeper way of seeing the world beyond the visible.

At 18, the death of her ten-year-old sister profoundly affected her. Art became, for her, a bridge between the living and the dead, the visible and the invisible. She felt guided by a divine force, something that moved through her, pushing her forward in her work and her life.

By the end of the 19th century in Stockholm, Hilma began participating in spiritualist séances, a popular practice across Europe at the time, especially among followers of Theosophy. Spiritualism aimed to communicate with spirits using tools like the psychograph (a kind of automatic writing instrument).

In 1896, at 34 years old, she founded "The Five" (De Fem), a spiritualist group formed with her friend Anna Cassel. Together, they became the originators of some of the first truly abstract artworks in history. This Christian spiritualist group merged their traditional faith with contemporary spiritual ideas. They met regularly for over a decade, leaving behind over 2,000 pages of notes documenting their spiritual sessions. They sought messages from higher spiritual beings. As a result, the women created automatic drawings — believed to be guided by spiritual entities, beyond their own control. Hilma would later represent these messages on large canvases.

Her greatest challenge became: how to represent the unrepresentable? How to give form to something that has no physical anchor in the material world? Applied to art, this meant inventing entirely new compositions, shapes, and colors to capture the supernatural. She believed that reality extended far beyond what the eye could see. Her life’s mission became to uncover and visualize these unseen dimensions.

Hilma never stopped practicing spiritualism and continued her explorations until her death in 1944. Misunderstood by her contemporaries, she asked her nephew in her testament, to only show her works 20 years after her death, which consisted of over 1300 paintings and hundreds of notebooks. It wasn’t until 1986 that the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles Museum of Art, finally brought her groundbreaking oeuvre into the public eye.

Today, Hilma af Klint is celebrated not only as a pioneer of abstract art, but as a visionary who fused science, spirituality, and imagination to create a body of work far ahead of its time.

2 artworks by Hilma af Klint

In September 1907, Hilma af Klint recorded a vision that spoke of “ten paradisaically beautiful paintings” meant to offer the world a glimpse into the journey of life. Just a month later, she began painting what would become The Ten Largest.

These monumental abstract works depict the four major stages of human life: childhood, youth, adulthood, and old age. Her deep connection to nature is reflected through botanical motifs, which intertwine with invented words and phrases, some said to be received from spiritual sources. In places, her text spirals across the canvas in bold, looping gestures, blurring the line between language, form, and mysticism.

In 1915, Hilma af Klint began The Dove, one of the final series of the Paintings for the Temple. In this series, she portrays circles and spirals, which hold deep spiritual meaning and are omnipresent in her works. She also portrays a dove, a symbol of the Holy Spirit and divine messenger, which appears in two of the works. This series blends symbolic color, abstraction, and clear figuration. It also features the mystical battle of Saint George and the dragon, a representation of light triumphing over darkness. Af Klint noted that Saint George was one of her alter egos.

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986)

Known as the “Mother of American Modernism,” Georgia O’Keeffe created a unique and powerful visual style. Starting from real subjects like flowers, bones, and landscapes, she simplified and transformed them into abstract, symbolic forms. Her famous large-scale flowers weren’t just botanical — they turned small, intimate details into something monumental and emotional.

At a time when the art world was dominated by men, O’Keeffe forged her own path. She rejected labels and followed her intuition rather than fitting into any specific art movement. Georgia O’Keeffe represents a unique side of abstraction: biomorphic, sensual, subjective, and meditative. Each of her works is, in its own way, an open doorway to inner reflection.

Her life in brief

Born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, Georgia O'Keeffe developed a deep connection to nature from a young age, which would become the central theme of her art. In her twenties, she studied art in Chicago and New York, but initially, she struggled with the idea of imitating the works of other artists, leading her to pause her painting for a while. It wasn’t until she discovered her “own way” through the teachings of Arthur Dow that she began creating abstract drawings.

In 1916, O'Keeffe sent her charcoal drawings to Anita Pollitzer, who then shared them with Alfred Stieglitz, a renowned photographer and the owner of the 291 gallery in New York. Stieglitz was immediately captivated by her work and decided to exhibit it. Their professional relationship soon blossomed into a romantic one. O'Keeffe's fascination with the natural phenomena of Texas, where she traveled to teach, played a significant role in shaping her art.

After spending time in Texas, she moved to New York, but she spent summers at Lake George, where she continued to explore her creativity. Throughout her career, she and Stieglitz influenced one another deeply, with O'Keeffe painting the joy she found in the world around her. She produced some of the most significant and original abstractions of American modernism, while Stieglitz took many photographs of her, including a series of nudes, for which she was later criticized.

O'Keeffe's art fused abstraction with elements of the real world, lending her work a sense of solidity and strength. In 1929, she spent the summer in New Mexico, where the arid landscapes and vibrant skies captivated her. There, she discovered her spiritual home in Abiquiu, which she would settle in after Stieglitz's death in 1946. Her work, known for its large-scale paintings of bright flowers, New Mexico desert landscapes, and animal bones, often depicted these subjects with abstract forms and an intense use of color.

Initially exploring watercolors with bold, expressive strokes, O'Keeffe eventually transitioned to oils. Her paintings reflect her deep connection to nature and her desire to capture the essence of organic forms.

O'Keeffe paved the way for women artists at a time when the art world was largely dominated by men. Her legacy lives on, symbolising artistic independence, creative daring and the ability to reinvent traditional genres.

2 artworks by Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe drew inspiration from her frequent visits to Alfred Stieglitz's family home, and aimed to depict the sublime landscapes of the region. This painting highlights O’Keeffe’s own avant-garde, abstract style and can be viewed both vertically and horizontally, creating a sense of ambiguity that makes it both representational and abstract. When first exhibited in 1923 at the Anderson Galleries, it was hung vertically, inviting comparisons to her enlarged flower imagery, which she was also exploring at the time.

Georgia O'Keeffe's "Red Canna" is a remarkable piece from her extensive flower series (she painted around 200 between 1920 and 1950). Painted in 1924, this artwork exemplifies O'Keeffe's unique approach to depicting flowers : by magnifying the red canna flower, she invites viewers to appreciate the intricate details and beauty that are often overlooked in smaller, everyday objects. This technique is characteristic of many of O'Keeffe's flower paintings, which have become iconic for their ability to transform the familiar into something extraordinary.

Jenny Saville (b. 1970)

When one looks at the nudes painted by Jenny Saville, it’s natural to think of Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud. But make no mistake. Where Bacon scratches flesh down to the bone to set the animal free, and where Freud bruises appearances to strip the human down to its essence, Saville does something else entirely. With her brush, she gently caresses the flesh beneath the skin, revealing the hidden landscapes of the human body. Mountains, rivers, forests, people, uncharted territories: she invites us on a deep and intimate journey.

Jenny Saville paints faces, and you find yourself moved by each one. She paints bodies, and you feel like you’re exploring a whole world. Her brushwork is both violent and tender, raw yet full of empathy. Saville transcends the boundaries between classical figuration and abstraction, turning flesh into terrain and vulnerability into power.

Her life in brief

Jenny Saville was born in 1970 in Cambridge, England. Between 1988 and 1992, she studied at the Glasgow School of Art. She once shared a memory from when she was six years old — sitting on the floor, watching her piano teacher's thick thighs move under her tweed skirt as she played music. That moment sparked her deep fascination with the human body — not the perfect version we often see, but the real one: soft, flawed, strong, and alive.

In 1994, she went to Connecticut for a fellowship, where she had the chance to observe a plastic surgeon in New York. She watched how human flesh was reshaped and rebuilt. This experience helped her understand the body’s strength and fragility. She also studied medical images, cadavers, animals, meat, classical sculpture, and the paintings of old masters like Titian.

Her big break came when art collector Charles Saatchi saw her graduate work and offered to support her. He gave her a studio and financial help, launching her career when she was just 22. Saville became known in the 1990s as part of the Young British Artists (YBAs), but she stood out. While others shocked people with ideas, she impressed with powerful painting — full of emotion, texture, and technical skill. In 1999, she had her first solo exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in New York.

Saville changed figurative painting by pushing the limits of how we see and represent the human body. Her work is a response to how women have been shown in art for centuries — often passive, delicate, and sexualized. Instead, she paints large, bold bodies that take up space and cannot be ignored.

Jenny Saville’s art is also political. She calls herself a "scavenger of images" and often uses photos and medical pictures — including surgery, scars, pregnancy, and more. Her work is about truth and change. It explores what it means to live in a body, especially a female one, in a world full of rules and expectations. She paints women who don’t fit the typical idea of beauty: women who are overweight, bruised, post-surgery, pregnant, transgender, or even deceased. She once said, “I want to be a painter of modern life, and modern bodies.”

Her paintings aren’t traditionally beautiful. They are raw, emotional, and real — full of thick brushstrokes that remind us of artists like Lucian Freud and Rubens, but with a strong feminist voice. Her work challenges how we see beauty, motherhood, gender, and control over our own bodies.

Jenny Saville is now seen as one of the most important figurative painters of her generation. She broke the old rules around how the nude is shown and created a new way of seeing bodies that are usually left out. In 2018, her painting Propped sold for £9.5 million, making her the most expensive living female artist at the time.

She continues to live and work in Oxford. Her recent work explores themes of motherhood, layered portraits of family members, and images of trans and non-binary people; showing that she is always evolving and tuned in to the world around her.

2 artworks by Jenny Saville

This painting is an unconventional female nude: a nearly obese body onto which she paints her own face. There is a deliberate dissonance between the body and the canvas, with exaggerated perspectives and a confident gaze. This shift challenges the traditional relationship between the artist and the model, the model and the viewer, and ultimately the viewer and the artist. In the end, it is about allowing the female artist to reclaim her art — and the female model to reclaim her body. This also exemplifies Saville’s technique and approach: she blends the abstraction of cubism with the sensuality of baroque, as no other artist has ever done before and includes elements of abstract expressionism with photographic figuration.

The word “odalisque” originally referred to a female servant or concubine in a harem, often romanticized in Western art as an exotic, sensual figure. Jenny Saville reimagines this figure in a bold, modern way. Instead of showing an idealized woman, she paints tangled, overlapping bodies using thick, expressive brushstrokes. The figures are raw, fleshy, and real — challenging the viewer’s ideas about beauty and the body. Her color palette is mostly skin tones, whites, and grays, with paint that sometimes drips, adding a sense of movement. The composition is busy and layered, making it hard to tell where one body ends and another begins. Saville flips the traditional image of the odalisque, confronting how women’s bodies are shown in art and asking us to see them with honesty and empathy.

Conclusion

What is common to the stories of these women is their resilience and their unwavering inclination towards life, rather than letting suffering define their existence. This stance, in opposition to death, was a deliberate choice, which materialized into sublime works of art. From this, I conclude that if they chose life, and in doing so chose art, then art must indeed be life. Art is life.

Each of these artists champions authenticity and truth. Their bold, singular voices have made lasting contributions to the art world and continue to inspire new generations of artists.