Famous Still Lifes in Art History: Masterpieces of Observation and Symbolism

Still life painting holds a significant place in art history because it allows artists to explore the elements of composition techniques and color use while interpreting symbolic meaning. Still-life painting progressed from Renaissance fruit compositions through to Post-Impressionist dynamic brushstrokes to tell deep stories about life, mortality and material culture. Despite receiving less attention compared to historical and portrait paintings still lifes have played a crucial role in shaping artistic methodologies and concepts.

Flemish Still Life: The Art of Vanitas

The 16th and 17th-century Flemish still-life paintings presented allegorical themes that conveyed life's transience together with the fleeting nature of wealth and pleasure. The 1630s "Vanitas Still Life" by Pieter Claesz represents a renowned work that displays symbols like skulls and extinguished candles to convey life's transient nature. The artist Pieter Claesz displayed remarkable ability to represent light effects and textures in his detailed renderings of shiny surfaces. Through detailed compositions Flemish artists demonstrated worldly beauty versus death's inevitability to convey moral and philosophical teachings.

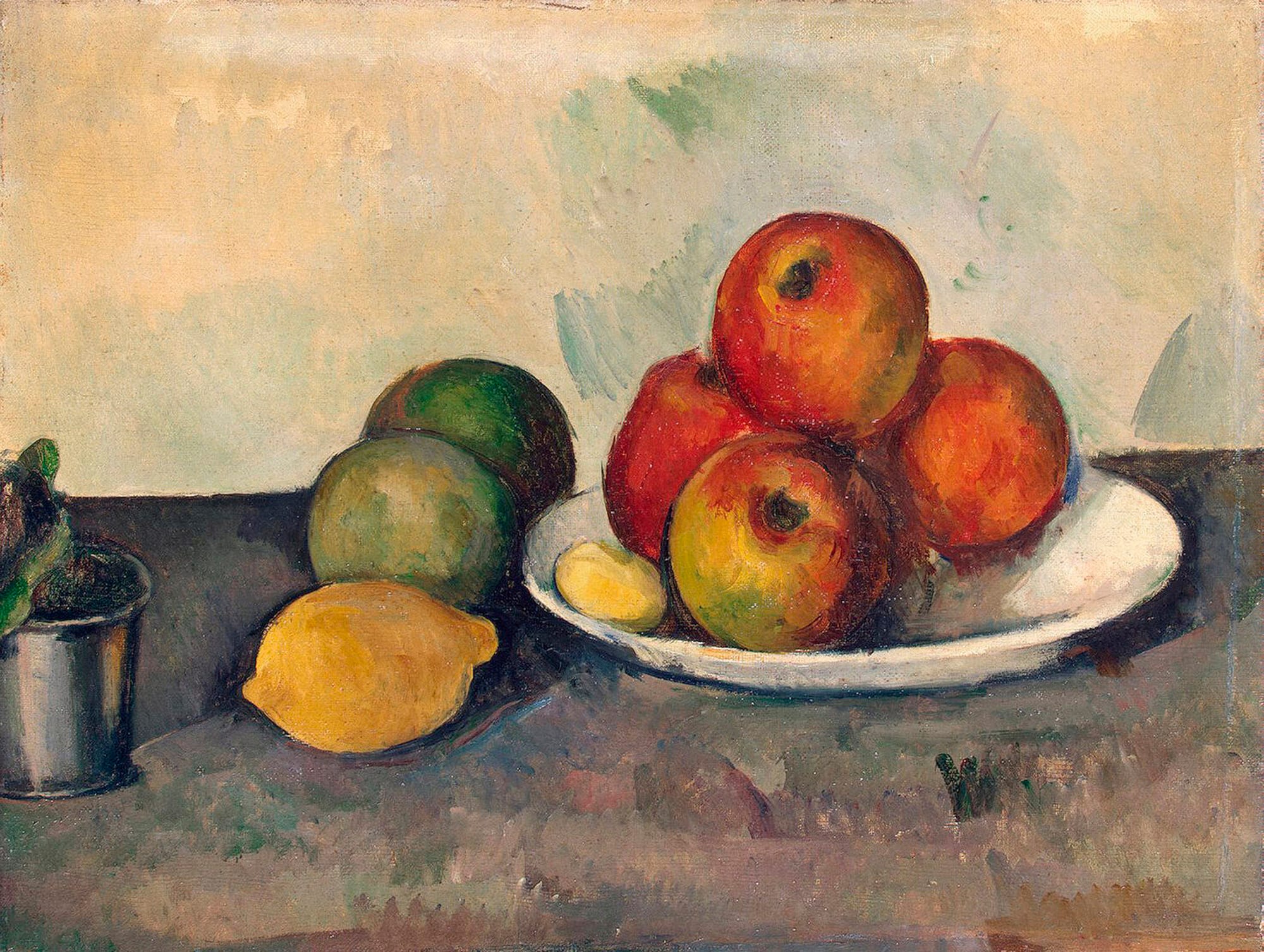

Paul Cézanne – Still Life with Apples (1895-1898)

The artist known as "father of modern art" Paul Cézanne transformed the still-life genre by implementing innovative techniques of form and perspective. Paul Cézanne's Still Life with Apples showed how basic objects could be broken down into geometric shapes to establish principles that later led to Cubism. Cézanne transformed traditional still-life paintings by emphasizing their structural elements to create a three-dimensional sculptural effect. His dynamic compositions emerged from multiple brushstrokes and changing perspectives to challenge the norms of static art representations. Cézanne's still life paintings went beyond basic representations of fruit and domestic objects through their study of spatial depth perception.

Vincent van Gogh – Sunflowers (1888-1889)

Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers series holds a position among art history's most recognized groups of still-life paintings. While living in Arles Vincent van Gogh created these paintings to decorate his artist friend Paul Gauguin's room. Van Gogh’s Sunflowers express potent emotions with textured brushwork and vibrant yellow hues resulting in dynamic movement which distinguishes them from conventional still life paintings. Selected versions featuring wilting flowers present themes of decay and temporality that grant these works symbolic meaning beyond simple ornamentation. Van Gogh's still lifes continue to resonate because he possessed the unique ability to infuse simple objects with profound emotional significance.

Édouard Manet – A Bunch of Asparagus (1880)

Through his innovative style in still-life paintings like A Bunch of Asparagus Édouard Manet became instrumental in shifting artistic expression from Realism towards Impressionism. Manet broke away from traditional detailed still-life art by using quick brush strokes to create a dynamic sense of immediacy in his works. The deliberate use of lighting and shadow effects combined with subtle color transitions turned ordinary objects into beautiful subjects. The spontaneous nature of Manet's still-life works revealed his relationship with the dynamic modern world he inhabited. Manet legitimized still life as an avant-garde artistic domain by defying established academic norms through his artistic practice.

The Role of Still Life in Flemish Art

The 16th and 17th centuries saw Flemish artists produce still-life paintings characterized by intricate detail which contained symbolic significance. Clara Peeters became an influential still-life artist by depicting luxurious arrangements of food items, flowers, and tableware as representations of wealth and achievement. Baroque period Flemish still lifes displayed rich opulence which opposed the simpler works created by Dutch contemporaries during the same era.

Jan Davidsz de Heem established his status as a Flemish master with his intricate banquet scenes and floral compositions that represented abundance. Through the combination of realistic details and theatrical effects his paintings achieved life-like qualities in otherwise inanimate objects. These artists used visual storytelling to convert still life into an expressive medium that examines luxury and mortality through nature's fleeting beauty.

Still-life painting traditions have remained relevant by adapting to different artistic movements and cultural developments throughout history. Artists like the Flemish masters utilized still lifes to achieve precise realism while Van Gogh used them to express vibrant energy and Cézanne developed structural innovations through this experimental medium. Contemporary art shows how the still-life genre keeps evolving by finding deep meaning in everyday objects.

Art history values still-life paintings for their continuous examination of life and death themes along with their analysis of color and form. The artworks encourage audiences to find beauty within common objects and to interpret deeper narratives from simple designs.