Famous Japanese Paintings and Artists: Iconic Masterpieces & Cultural Heritage

From the stark ink washes of Zen monks to neighborhood emojis of Yayoi Kusama, Japanese painters have shown that a single brushstroke can carry centuries of belief, politics, and craft. Their work continues to sell out museum shows, drive scholarship, and inspire filmmakers and game designers alike. The reasons are straightforward: clear visual language, technical rigor, and an eye for everyday scenes that feel universal.

A Five-Minute Timeline of Japanese Painting

Early Buddhist & Yamato-e (7th – 12th c.) Monks used mineral pigments on silk scrolls to spread sutras and moral tales. In court circles, Yamato-e stories such as The Tale of Genji handscrolls paired delicate colors with swift narrative cuts.

Muromachi Ink & the Zen Revolution (1336 – 1573) Zen abbots like Sesshū Tōyō swapped color for charcoal-black sumi, showing how “nothingness” can be rendered with controlled splashes of ink. The technique later appears in wash painting, a term we unpack in our Art Glossary.

Momoyama Opulence & the Kano School (1573 – 1615) War-torn lords wanted intimidation and glitter. Kano Eitoku answered with gold-leaf folding screens wide enough to cover a castle hall.

Edo’s Ukiyo-e Boom (1615 – 1868) Cheap woodblock prints of kabuki actors and tourist spots turned painters into pop-culture stars. Hokusai and Hiroshige led, influencing Monet and Van Gogh far beyond Japan.

Meiji to Reiwa: From Nihonga to Superflat (1868 – today) Restoration leaders pushed Western oil painting; the Nihonga movement pushed back with updated mineral pigments. Post-war, Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara flattened manga imagery into luxury-brand collaborations.

Ten Paintings Everyone Should Know

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (The Great Wave) — Katsushika Hokusai, 1831

No single image sells Japan abroad more than this cresting wave, printed on cheap mulberry paper and sold to Edo tourists. A first-edition impression now lives at the Met in New York.

Fine Wind, Clear Morning (Red Fuji) - Hokusai

Mount Fuji glows brick-red at dawn, reminding Edo viewers that sublime moments can be caught on a hand-sized sheet of paper.

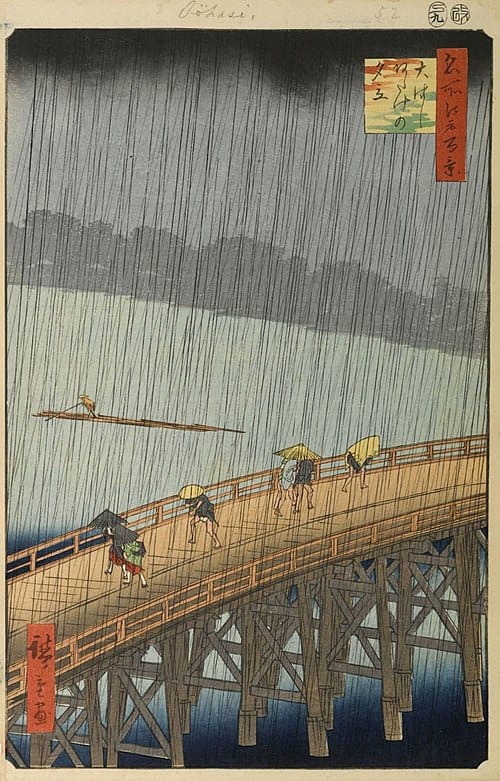

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge - Utagawa Hiroshige, 1857

Diagonal rain slashes across commuters’ straw hats, capturing a fleeting downpour in four carved woodblocks.

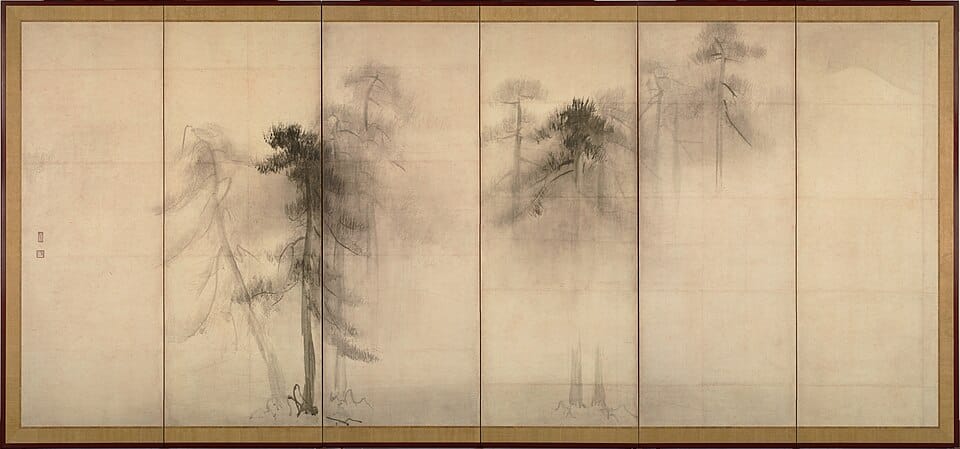

Pine Trees - Hasegawa Tōhaku, late 16th c.

Two six-panel screens drift in and out of mist, proving how monochrome ink can suggest entire landscapes. Today, they are a National Treasure at the Tokyo National Museum.

Irises at Yatsuhashi - Ogata Kōrin, c. 1710

Kōrin’s gold-leaf screens reduce flowers to bold shapes, a design language later borrowed by Art Deco. The Met featured the pair in its 2015 “Discovering Japanese Art” survey.

Heiji Monogatari Emaki: Night Attack on the Sanjō Palace, 13th c.

A 60-foot narrative scroll unrolls like modern-day storyboards, freezing a 1159 coup with cinematic cuts and crowd scenes.

Wind God and Thunder God -Tawaraya Sōtatsu, c. 1624

Two storm deities hover on separate screens, a playful balance of symmetry and negative space.

Rooster and Hen with Hydrangeas - Itō Jakuchū, 1750s

Jakuchū’s birds show microscopic feather detail alongside almost abstract background grids, a style beloved by contemporary collectors.

Lake Biwa in the Rain - Yokoyama Taikan, 1909

Nihonga revivalists like Taikan reintroduced mineral pigments, giving this twilight lakescape its deep blue haze.

Endless Net - Yayoi Kusama, 1959

Years before her mirrored rooms, Kusama painted near-infinite dots, arguing that obsession itself could be a subject.

Influential Artists, Era by Era

Ancient & Medieval Sesshū Tōyō turned Zen discipline into bold ink landscapes. Kano Eitoku filled warlords’ halls with outsized gold screens.

Edo Innovators Hokusai, Hiroshige, Ogata Kōrin, and Itō Jakuchū exported ukiyo-e prints and Rinpa design across the world.

Meiji Reformers Yokoyama Taikan and Takeuchi Seihō blended Western perspective with Japanese materials, founding modern Nihonga.

Post-War Visionaries Yayoi Kusama and Tadanori Yokoo used repetition and pop graphics to critique consumer culture.

Superflat & Neo-Pop Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara flattened folk toys and manga into global luxury-art hybrids.

Symbols, Materials, and How They Work Together

Ink to Mineral Pigments A suibokuga ink wash starts with soot and glue; a Nihonga red can come from crushed azurite. Both marry chemistry to philosophy.

Gold Leaf & Folding Screens Byōbu screens were portable partitions and status symbols. Their reflective surfaces brightened candle-lit castles and Zen temples.

Motifs & Symbolism: Mount Fuji, Koi, Sakura Mount Fuji implies permanence; koi carp stand for endurance; cherry blossoms remind viewers of life’s short curve.

Japonisme Abroad French Impressionists copied Hiroshige’s rain scenes; Art Deco designers borrowed Rinpa flat color and asymmetry.

Where to View These Masterpieces Today

Tokyo National Museum Houses Tōhaku’s Pine Trees and rotating Edo screens. Check current rotations before you fly.

Kyoto National Museum & Local Temples Nishijin-area temples still display screen pairs during annual festivals.

International Highlights The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston all maintain strong ukiyo-e rooms.

Digital Archives & VR Tours The Tokyo National Museum’s official site offers zoom-able gigapixel scans; the Met makes high-resolution prints free to download.

The Hard Work of Keeping Paper Alive

Japanese screens stretch paper over cedar lattices. Conservators monitor light, humidity, and insect damage, often restretching every few decades. The Met and TNM now use Murakami-style facsimiles for crowd-heavy shows to spare fragile originals.

Collecting Responsibly

Auction houses authenticate signatures, but provenance matters more: Edo prints were mass-produced, making pristine first pulls rare. Verify export licenses and avoid works lacking post-1950 paperwork to steer clear of wartime loot issues.

Quick Glossary

- Byōbu — Folding screen

- Nihonga — Modern painting using traditional pigments

- Ukiyo-e — “Pictures of the floating world,” mass-market woodblock prints

- Suibokuga — Zen ink-wash painting

The Living Legacy of Japanese Painting

Japanese painting has never stood still. Each generation absorbs outside ideas—Chinese ink, European perspective, digital infinity—then folds them back into local craft disciplines. The result is an art tradition that feels both ancient and startlingly current, ready for the next eye that cares to look. Explore our own painting space to see how today’s artists continue the conversation.