Masks, witches, a pumpkin: a quick tour of Halloween in art

Me, I’ll always have a soft spot for Maclise’s party—less horror, more human. But October belongs to multiple moods, and art has room for all of them.

October isn’t a genre. It’s a mood—foggy at the edges, oddly funny. Painters have been mining that mood for centuries.

Famous Halloween paintings

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare (1781). A woman sleeps; an incubus sits on her like bad news; a horse peers through the drapery as if it knows the ending. Romanticism invents a jump scare—and it still works.

Francisco Goya, Witches’ Sabbath (The Great He-Goat) (1820–23). A coven gathers around a horned silhouette. The paint looks rubbed with ash. It’s less “boo!” and more “this is who we are when the candles go out.”

Salvator Rosa, Witches at their Incantations (c.1646). Baroque horror as stagecraft: bellows, bones, smoke. You can almost hear a director shouting, “More cauldron!”

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring (1891). Two bony idiots argue about lunch while wearing carnival masks. Ensor’s joke: the living are no less ridiculous.

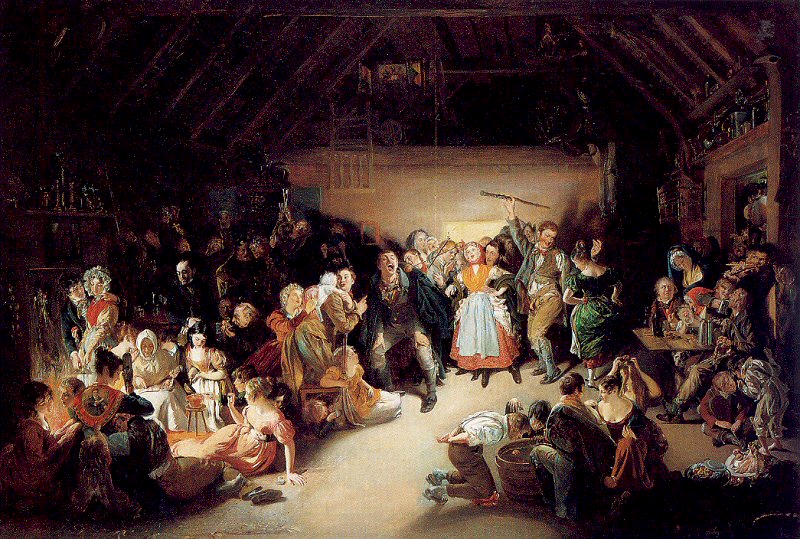

Daniel Maclise, Snap-Apple Night (All Hallows’ Eve) (1833). An actual Halloween party: bobbing for apples, fiddles, flirting. The only painting on this list where you could walk in and not die of fright.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Oiwa (Yotsuya Ghost Story) (1892). A lantern reveals the wronged ghost: long hair, ruined eye, a face that floats like a memory you didn’t want back. The template for so many modern hauntings.

Famous “Halloween” artists

Fuseli gave fear a posture. The demon sits, you squirm. Goya painted witchcraft the way people talk after midnight: bold, messy, too honest. Rosa staged evil with props and lighting—proto-cinema. Ensor swapped dread for satire; his masks tell the truth our faces won’t. Yoshitoshi (and Kuniyoshi before him) fixed the visual language of ghosts: limp limbs, loose hair, that lantern glow. Edvard Munch isn’t “Halloween,” strictly—but The Scream is October’s ringtone. Yayoi Kusama turned pumpkins into quiet mysticism. Dot by dot, a folk object becomes a universe.

Witches, skeletons & spectres: a very short history lesson

Seventeenth-century Europe loved a good fright with footnotes. Rosa stacked his canvases with ingredients—relics, herbs, unsayable things—so you’d believe in the ritual. A century later Fuseli cut the props and went psychological: get inside the nightmare, don’t narrate it.

Then Goya, at the end of his life, paints witch scenes on his walls. Not theater—confession. No moral, no tidy frame. The air is heavy and modern.

North of Spain, Ensor watches his neighbors and thinks: skulls with opinions. He makes death social. Which is both mean and fair.

Across the world, Yoshitoshi draws Oiwa from kabuki lore. The image—hair like wet weeds, a face sliding out of alignment—carries forward into film, manga, TikTok filters. Ghosts become exportable.

If Halloween has a “look,” it’s really a slow conversation between these studios. Smoke to psychology to satire to archetype.

Where to see them, because screenshots aren’t the same

- The Nightmare — Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit.

- Witches’ Sabbath (The Great He-Goat) — Museo del Prado, Madrid.

- Witches at their Incantations — National Gallery, London.

- Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring — Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

- The Scream — National Museum and MUNCH, Oslo (rotations apply; check which version is up).

- Oiwa prints — British Museum, London; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

Tip from me: give The Nightmare two visits—one quick pass, then a long stare. The horse’s eyes are funnier the second time.

Modern pumpkins (seasonal, yes; easy, no)

Kusama’s pumpkins aren’t about harvest or décor. They’re stand-ins for attention itself—patterned repetition that calms the eyes and makes you wonder where the edges are. On Naoshima, her big yellow Pumpkin sits by the water like a buoy for the brain. In museums, smaller pumpkins turn into mirrors: you watch the dots, the dots watch back.

FAQ (because someone will ask)

Are there “official” Halloween paintings?

Only a few. Maclise painted All Hallows’ Eve by name. Most of what we call “Halloween art” uses its cast—witches, ghosts, masks, skeletons—without the holiday label. That’s fine. Fear travels.

What if I hate gore?

Good news: the smartest Halloween pictures aren’t about blood. They’re about mood, posture, light. Fuseli and Munch are almost clinical about it.

Where should a newbie start?

One from each shelf: Fuseli for the classic shock; Goya for the uneasy laugh that comes after; Ensor for satire; Yoshitoshi for a perfect ghost; Kusama to exit with steadier breathing.

If Halloween is a house, these are the rooms: theater, dream, politics, gossip, folklore, pattern. We move through them every October—sometimes for a shiver, sometimes for a laugh—and art, kindly, leaves the lights halfway on.