France: Four Centuries of Restless Looking

France’s hold on the Western imagination is less a question of geography than of perception. From the moment Francis I began luring Italian masters north of the Alps, French painters have treated the canvas as a testing ground for new ways of looking—at light, at flesh, at the machinery of thought itself. The story that follows is not a tidy genealogy so much as a chain reaction: each generation detonates some fresh visual device, and the aftershocks travel far beyond Paris. What results is a four‑act drama whose reverberations still shape the way we read a museum label—or the clouds over the Seine—today.

The Renaissance and Baroque: French Art in the Early Modern Period

Claude Lorrain (1600–1682)

Claude Lorrain was technically from Lorraine, but his true homeland was the sun. Stand before Seaport at Sunset (1639) in the Louvre and the picture doesn’t merely describe twilight—it conducts it. A molten disk hovers just above the horizon, bleeding amber across a harbor where marble ruins crumble in dignified silence. Masts tilt toward the glow like tuning forks searching for pitch, and the water shivers with mirrored gold. Nothing important happens in the human sense; ships load cargo, a shepherd drifts in from the right. Yet the painting feels monumental because Lorrain treats light itself as narrative. Before him, landscape had served as backdrop. After him, it became the plot.

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

Nicolas Poussin, born five years earlier, offers the skeptical counterpoint. In Et in Arcadia Ego (1637–38) a quartet of shepherds kneel at a weather‑beaten tomb, their fingers tracing an inscription that reminds even the carefree that death keeps an address in paradise. Poussin arranges their bodies like chess pieces on a diagonal grid—each gesture echoes another, each color damped to a measured chord. Hang around long enough and you start to feel the painter’s real subject is not mortality but order: geometry as consolation, clarity as a stay against panic. Where Lorrain dissolves form in radiance, Poussin locks radiance behind logic’s gate, proving a cool head can accommodate a hot subject.

Rococo to Neoclassicism: Refinement Meets Order

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

A century later the pendulum swings toward silk and sighs. Jean‑Antoine Watteau’s fête‑galantes flutter like chiffon caught by a breeze, and Pilgrimage to Cythera (1717) is his most gossamer hallucination. Lovers in apricot satins drift downhill toward swan‑prowed barges, while cherubs sprinkle rose petals overhead. Watteau’s brush describes surfaces so lightly you half‑expect the pigment to float off the canvas. Yet pay attention to the shadows pooling under those satins and you’ll sense regret sliding beneath the gaiety, a premonition that the voyage home will be lonelier than the trip out.

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825)

When revolution looms, chiffon will no longer do. Jacques‑Louis David snaps the Rococo harpsichord shut with The Death of Socrates (1787). The scene is marble‑hard virtue: the philosopher reaches for the hemlock cup while disciples collapse around him, their limbs zig‑zagging through space like collapsing scaffolds. David scores the composition with trap‑door blacks and judicial whites; even the drapery looks quarried rather than woven. This is not ornament but obligation—painting enlisted as a manual for upright living at the brink of upheaval.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806)

Yet even amid civic thunder, Jean‑Honoré Fragonard keeps the Rococo torch flickering. The Swing (1767) is a powder‑scented scandal: a young woman hurtles skyward, skirts billowing like a cumulus, as her hidden lover peers into the ruffled mystery beneath. Sunlight needles through leaf‑screens, lighting her silk in fizzy pinks; each brushstroke feels less painted than giggled. But look closer and the foliage seems to curl into baroque arabesques, as though hinting that pleasure, too, obeys a choreography—and that flirtation can be as regimented as any drill square.

Impressionism: A Revolution in Seeing

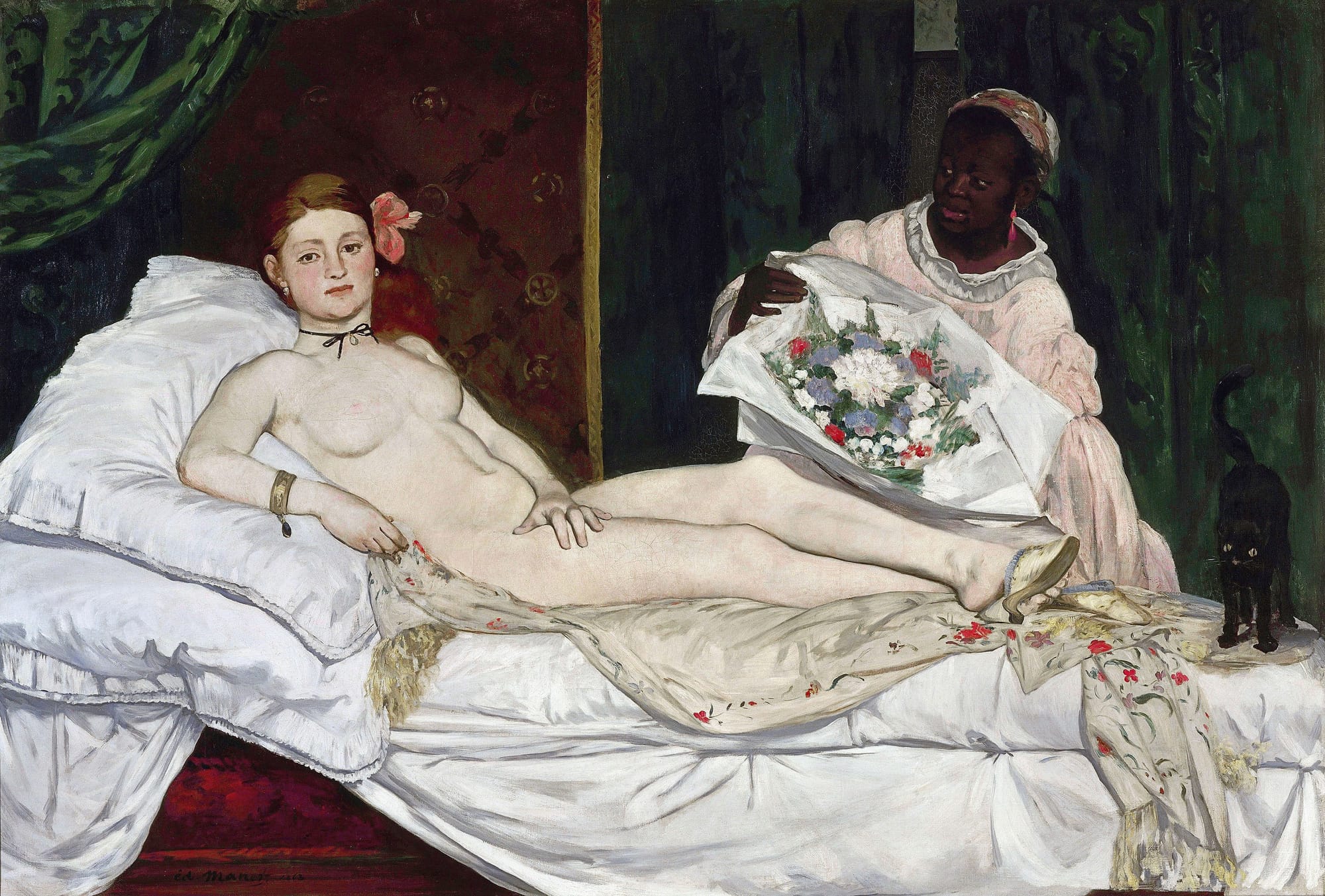

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Édouard Manet pries the 19th century open like a fresh oyster. In Olympia (1863) a nude courtesan lies propped on her elbow, meeting the viewer’s eyes with a look so wired it feels Bluetooth‑enabled. Gone is the Renaissance haze; Manet paints in crisp front‑of‑house lighting, flattening the body into zones of ivory, rose, and blue‑black shadow. The black cat at her feet arches its spine in sly echo of the painter’s defiance—modernity has arrived, tails up.

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Claude Monet answers defiance with devotion—to weather, to optics, to time’s pulse on water. Impression, Sunrise (1872) loans its title to an entire movement, yet the canvas could fit in your carry‑on. A tangerine sun hovers over Le Havre’s misty port; its reflection slices the gray harbor with a tremor of pigment so thin it feels breathed, not brushed. Looming cranes dissolve into atmosphere, making industry look like something the tide washed in at dawn. Monet records no objects—only conditions, always escaping.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919)

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir supplies the countermelody, coaxing warmth from a brush that barely seems to touch the linen. Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881) gathers friends on a riverside terrace thick with beer foam and banter. Straw boaters tilt at rakish angles; a puppy noses a breadbasket; enamel light bounces off metal railing into white tablecloths. Renoir’s palette runs to apricots and butter yellows, colors that taste like picnic desserts, but the real flavor is tempo—figures overlap in a staccato rhythm that makes conversation visible.

Post‑Impressionism and Modernism: Pushing the Boundaries

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Paul Cézanne, Impressionism’s reluctant heir, swaps Monet’s shimmer for scaffolding. In The Bathers (1898–1905) nude bodies huddle beneath vaulting trees whose trunks bend like architectural ribs. Flesh, foliage, even sky are chunked into calibrated facets of ocher and powder blue; perspective grips and slips at once. The picture is less a scene than a theorem, one that whispers of Cubism to come: everything may be rebuilt if you first break it into planes.

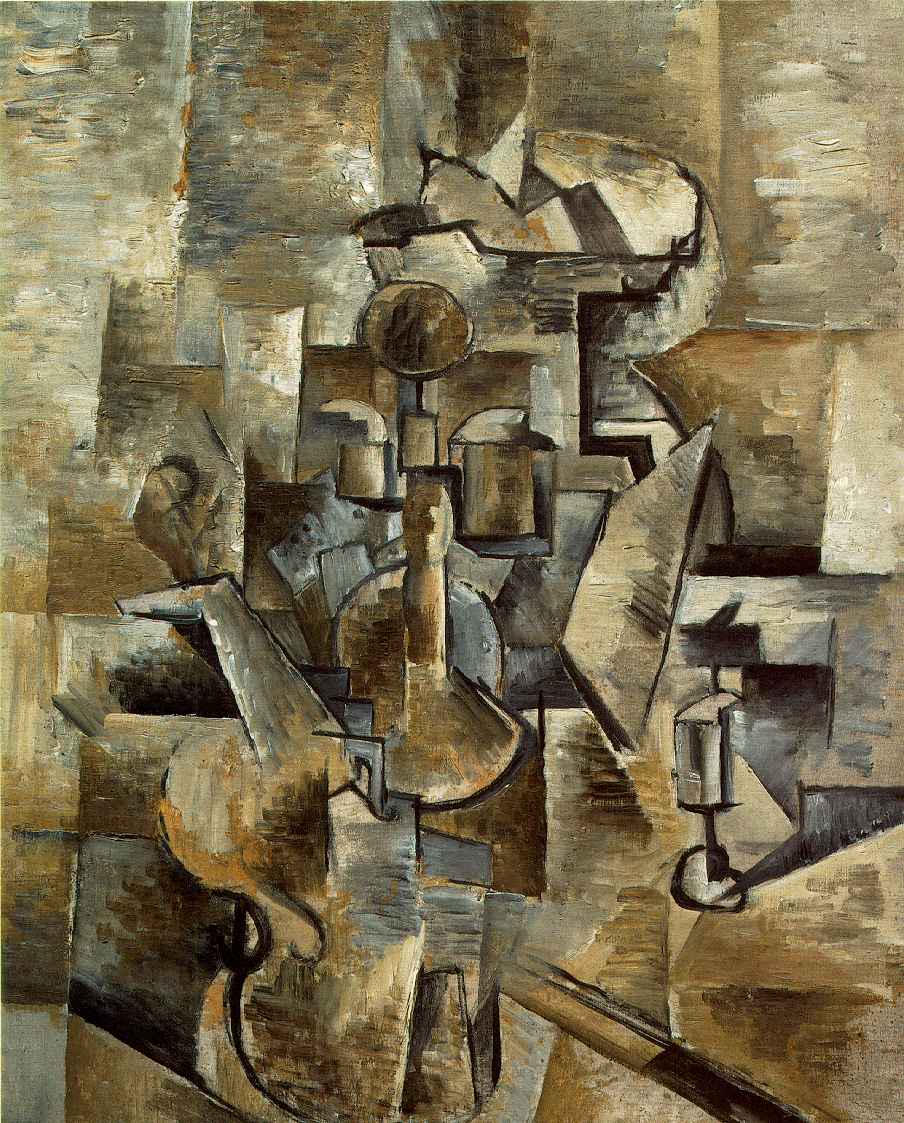

Georges Braque (1882–1963)

Georges Braque hears that whisper and replies in shards. Violin and Candlestick (1910) fractures its subject into an exploded diagram of grays and ochers—scrolls of the f‑hole, a bulb of waxy flame, the ghost of a scroll. Braque refuses the old bargain of single‑point perspective; instead he offers time, thought, and multiple points of view laminated into one surface. You see the instrument, the light around it, and the intervals between glances—all at once.

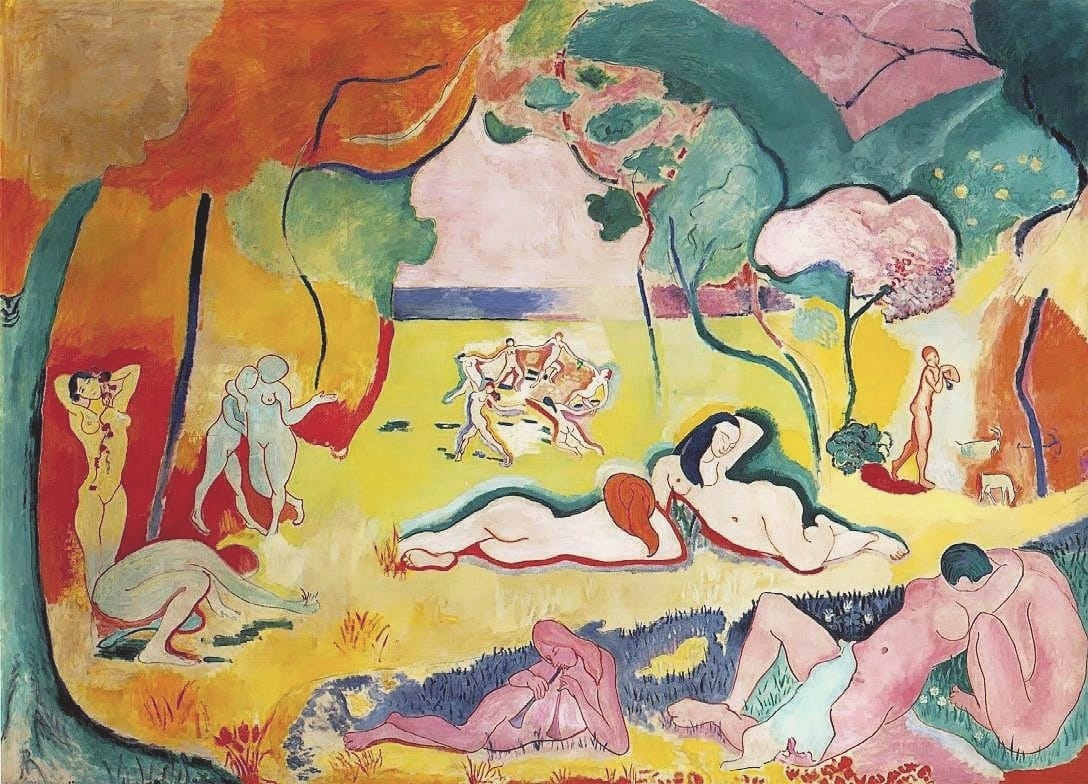

Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

Swinging the pendulum back toward pure chroma, Henri Matisse detonates color. The Joy of Life (1905) sprawls over six square feet yet feels boundless: nudes recline, dance, or stretch beneath candy‑orange trees; a lagoon of mint green carves a lazy C through the middle. Lines loosen like garden hoses in July, and pigment sings in unmixed jolts of cadmium. The scene is pastoral only on paper; in practice it’s a riot of pigment staging a coup against outline.

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

Then Marcel Duchamp flips the table—and perhaps the century. By submitting a porcelain urinal titled Fountain (1917) to an independent exhibition and signing it “R. Mutt,” Duchamp relocates authorship from studio to brainpan. The object is store‑bought, the gesture store‑ys high: What is art if not intention grafted onto matter? If Cézanne built the modern house, Duchamp removed the floorboards and invited us to hover, making every subsequent painter ask whether lifting a brush is even necessary.

French painters never agreed on what a picture should be; they only agreed it must stay alive. From Lorrain’s molten skies to Duchamp’s porcelain joke, each generation rewrote the rules it inherited. Their quarrels left us a legacy of restlessness—and the hard, exhilarating pleasure of trying to keep up.