Why the Clown Won’t Leave the Canvas

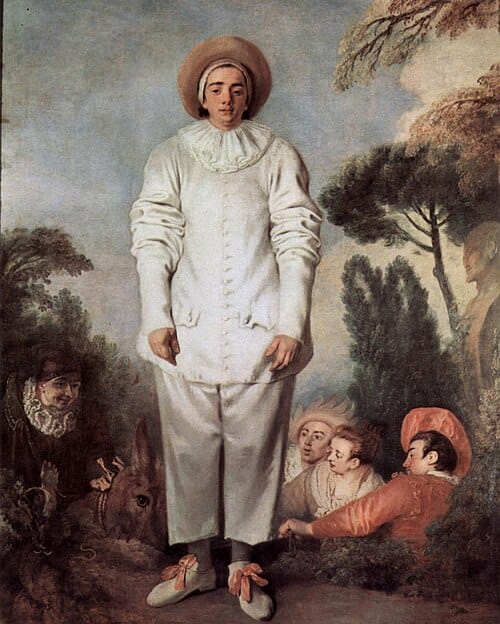

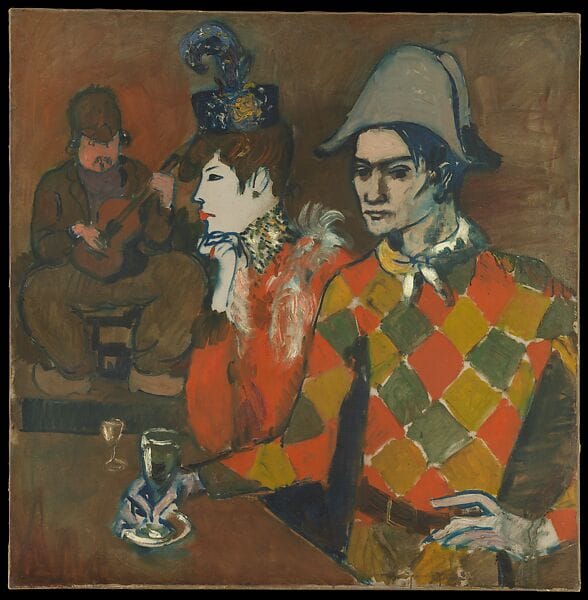

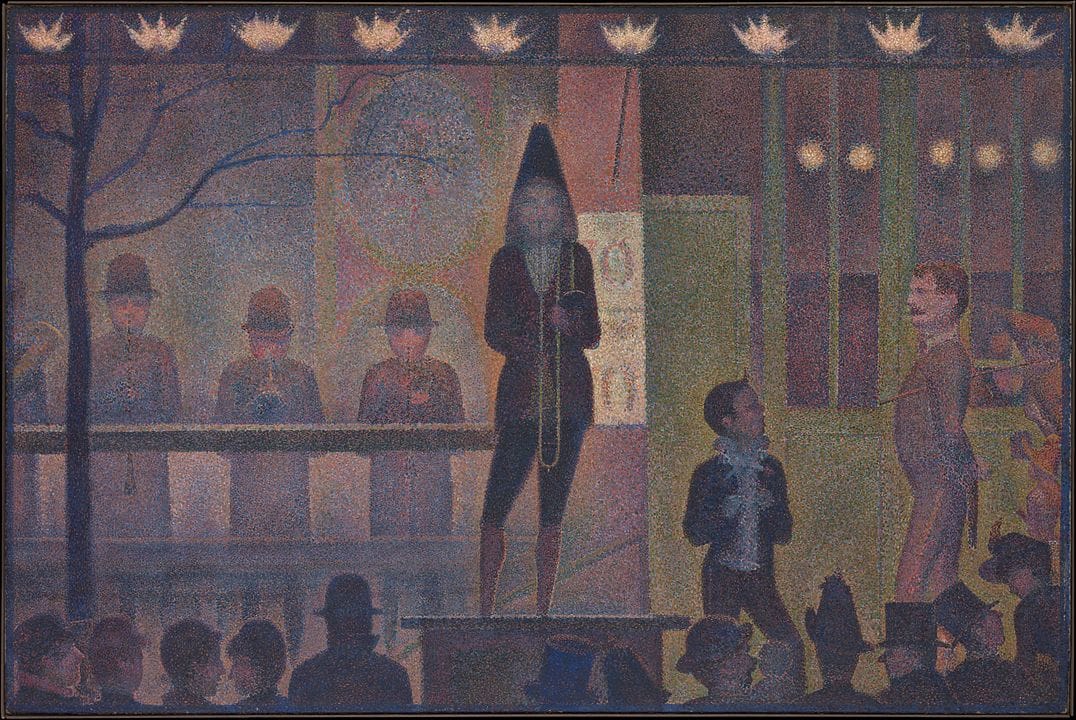

The room is dim. A clarinet calls from the curb. On Seurat’s stage, the act hasn’t started—yet the mask is already doing its work. Clown paintings aren’t comic relief; they’re rehearsal rooms for feeling. Watteau gives us the lunar hush of Pierrot; Picasso tries on Harlequin like a second skin. Look long enough and the greasepaint thins. What’s left is role, risk, and the small drama of being seen.

Quick answers for the impatient

The one everyone means. Watteau’s Pierrot (Gilles) — the big, pale face at the Louvre that seems to breathe. Close seconds: Picasso’s At the Lapin Agile and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow.

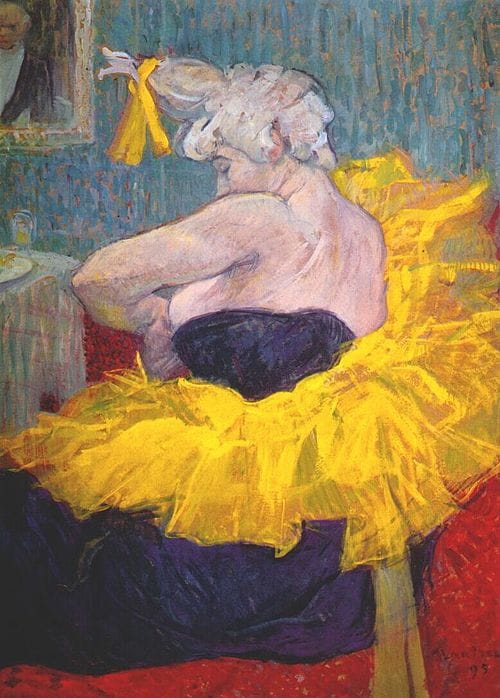

Who painted the clowns we actually talk about? Start with Watteau (sets the template). Then Picasso (Harlequin as alter ego), Seurat (the hush before the show), Toulouse-Lautrec (backstage truth). Echoes later: Rouault, Klee, Miró, Ensor, Buffet.

Pierrot vs. Harlequin, in one breath. Pierrot = unmasked, linen white, wistful. Harlequin = diamond suit, half-mask, quick on his feet.

A 10-second quality test. Find the edges (Rouault’s heavy black, Cézanne’s seams) and the light (Seurat’s gas-glow). If the picture only pleads sadness, not structure—keep moving.

Where to see them (without guessing). Louvre (Watteau), The Met (Picasso, Seurat), Musée d’Orsay (Lautrec). Hit the museum object pages for current display status.

Ten Famous Clown Paintings

Antoine Watteau, Pierrot (Gilles), 1718–19 — Louvre (Paris) A monumental sad clown, front and center, quiet as snowfall.

Pablo Picasso, At the Lapin Agile, 1905 — The Met (New York) Harlequin at the bar: theater meets fatigue in rose tones.

Georges Seurat, Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque), 1887–88 — The Met The show’s prelude: pointillist hush, gaslight, a clarinet pulling coins.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Clownesse Cha-U-Kao, c. 1895 — Musée d’Orsay (Paris) Presence and poise; a performer who meets your look head-on.

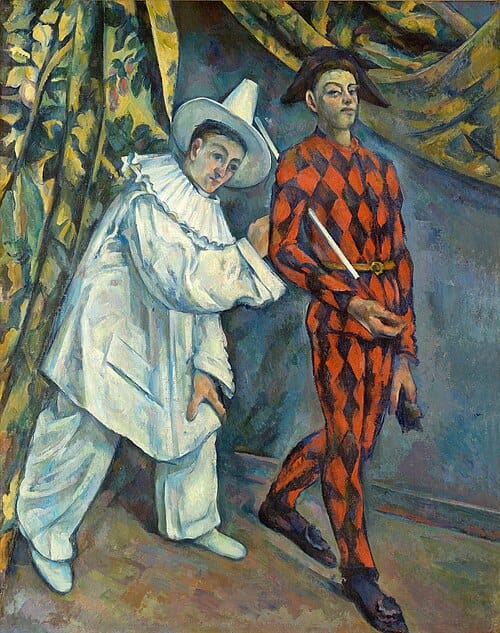

Paul Cézanne, Mardi Gras (Pierrot et Arlequin), 1888–90 —

Costume as structure; emotion built from planes.

Georges Rouault, Clown, 1912 — MoMA (New York) Stained-glass solemnity; comedy recast as icon.

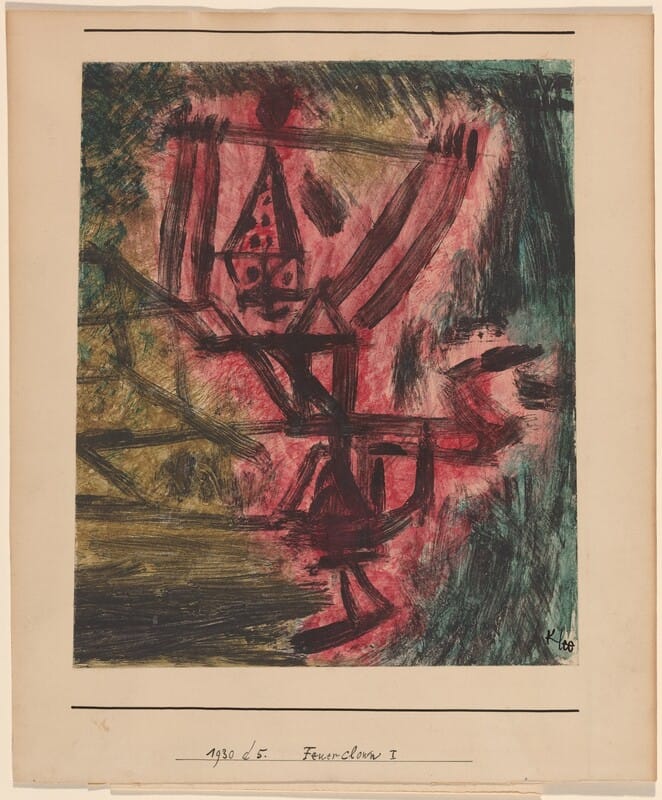

Paul Klee, Feuer Clown I (Fire Clown), 1921 — National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) A figure scored like music; line becomes rhythm.

Joan Miró, Harlequin’s Carnival, 1924–25 — Buffalo AKG (Buffalo) The carnival goes cosmic; signs dance where bodies once stood.

James Ensor, Pierrot and Skeleton in a Yellow Robe, 1893 — MSK Ghent Pierrot meets memento mori; comedy with a chill.

Bernard Buffet, Clowns (series), 1950s–60s — various collections Angular faces, mascara like armor; postwar ennui in greasepaint.

Pierrot vs. Harlequin — a pocket guide

Pierrot — unmasked, linen white, sleeves a touch too long. Moon-pale, often wistful. The pause between lines. Harlequin — diamond suit, quick mind, half-mask. Performance as attitude. The plot in motion.

Spot the Harlequin (10-second checklist): diamonds; mask; tilted pose; eyes that look past you, not at you. Slow looking tip: on Pierrot, watch the edge where costume meets shadow. Does the quiet feel earned?

Artists to Know (Watteau to Buffet)

Watteau turns a stock character into a modern everyman. The fête galante stops talking; Pierrot listens for us.Picasso wears Harlequin the way actors wear a role—on and off for decades. Identity as costume change.Seurat is all about the prelude: the economy of night, the discipline of waiting. We hear the hush.Toulouse-Lautrec catches what stages conceal—labor, nerves, and the body that does the work.Cézanne strips pattern to structure. Even the prankster stands still for a grid.Rouault paints clowns like saints with bruised haloes—thick black contours, compassion heavy as lead.Klee writes a figure the way one might write music; the joke becomes notation.Miró explodes character into signs—Harlequin’s spirit without the seams.Ensor drags carnival into the uncanny; masks over masks, a theater of anxiety.Buffet draws the face as architecture—hard angles, long lines, feeling held at arm’s length.

Collector’s Notes: quality vs. kitsch

- Iconography matters. Named archetypes—Pierrot, Harlequin, saltimbanques—age better than generic “sad clown” tropes.

- Painterly intent. Look for structure or a language of line: planes (Cézanne), stained-glass contours (Rouault), coded pattern (Klee).

- Provenance beats pathos. Catalogues raisonnés, museum citations, scholarly references.

- Market reality. Masterworks are museum-bound; quality later works, studies, prints, and school pieces surface at auction.

FAQ

Who is the most famous “clown painter”? Picasso is the popular answer—Harlequin haunts his Rose Period and beyond. For foundations, start with Watteau’s Pierrot.

What’s the single most famous clown painting? Watteau’s Pierrot (Gilles), with runners-up in Picasso’s At the Lapin Agile and Seurat’s Circus Sideshow.

How do I tell Pierrot from Harlequin? No mask vs. half-mask; plain white vs. diamonds; stillness vs. mischief.

Is “famous clown art” always sad? Not really. The best works balance irony with tenderness. The joke, if there is one, tends to be on us.

Are clown paintings a good buy? Iconic names carry the category. For living artists working this motif, look for clear ties to theater history and a language of form that’s their own.

We pretend clowns hide behind paint. Mostly, it’s us. That’s why these pictures keep working—centuries on, in rooms that fall quiet for a face in chalk white and a pair of eyes that won’t quite blink.