Curator. The Decision to Care

“We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.”— Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

We live immersed in information — and it’s exhausting: newsletters, blogs, social feeds, chats, ads. While being bombarded with desaturated meanings, we slowly suffocate.

There’s ongoing talk about “going and touching grass” or “switching to a flip phone.” Some dream nostalgically about Y2K as if it were a time of liberation and golden vibes. The funny part is that this dreamy reminiscing sometimes misleads us into thinking that retrogression is actually a solution.

But I think what we’re really longing for is the feeling of meaningful connection — and some control over our worldview — that we’ve lost repeatedly not only as individuals, but as a society: first by making God irrelevant, then science relative, and finally proclaiming meaning unnecessary. That nostalgic longing has become a kind of “epochal shift” marker, defined by a lingering emptiness we are desperate to fill.

So “touching grass” isn’t about believing that our backyard can cure anxiety. Rather, we believe in something that might help us shift our attention outward — and make possible a reconnection with something larger, something sublime — because nothing else seems able to.

But as we chase ever-shifting trends of global culture industries, our attention drifts. We read more news than ever, consume more information than any previous generation, and even wear “chronically online” as a badge of being culturally fluent. Yet when asked about the meaning behind the tons of information we consume, only shallow, ready-made answers resembling a hashtag come to mind.

Information that once built our worldview now clutters it. It blurs the outlines of our tastes, beliefs, and values — making it easier for trends to be pushed onto us while exploiting our attention for profit.

As an outcome, we grow numb — to experience, to feeling, to thought, to reflection. We grow anxious. We get tired. So we can’t focus our attention on something we choose for ourselves, but on something we’ve been trained to like and consume.

Now let this settle for a bit: we are willingly letting go of the right to be relevant and respected as independent individuals. In other words, we’re giving up on being seen and heard as ourselves. All because we are frustrated and worn down by systematic information anarchy.

Which leaves us asking: can we do anything to change it?We already do, even if we don’t always name it: we curate.

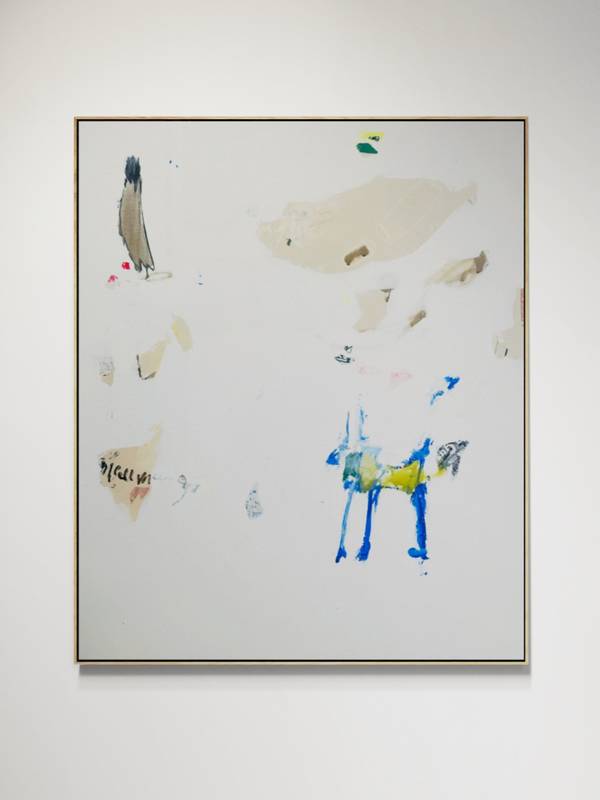

Curation may seem like the work of art dealers — selecting a piece for a collection, deciding on the next exhibition. But as Hans Ulrich Obrist reminds us in The Art of Curation, the word derives from the Latin curare — “to take care.”

Historically, the curator was entrusted with responsibility of taking care — be it public baths in ancient Rome, the souls of believers in medieval times, or the museum and its exhibits during the Enlightenment, and yes, of art galleries and private collections.

Today I see it used more often as a way of saying, “I’m in power to create and develop my own personality, despite the trends of mass media.” As if taking care of one’s authenticity. Perhaps we live in a time when we have become curators of the most important thing we own — ourselves.

And it makes sense. Because by curating what we consume, and to what we give our attention, we cultivate both our aesthetics and our ethics — while staying connected to the world rather than drowning in it.

So instead of growing numb — to experience, to feeling, to thought, to reflection — instead of growing anxious and tired, each of us now bears responsibility to curate our lives. And it is a deliberate act that shapes the world around us — our homes, our friend groups, our workplaces, our cities.

The decision to care — and to find something meaningful enough to care about — is what helps us overcome the lingering emptiness. Instead of losing the will to be ourselves because it takes too much effort, too much time, instead of shifting our preferences toward whatever we know will help us to fit in.

In the past, we overcame the distrust in religion during the Renaissance with the Enlightenment. We met the fall of positivism with Romanticism. We answered the poststructuralist loss of meaning by returning to our roots, communities, and environmental studies.

Now it’s time to reclaim authenticity — through art, through education, through public debate. Through anything that produces ideas strong enough to grow into ideologies. Ideas that stand for intellectualism and political awareness, for freedom and constant liberation.

Therefore, learn something new, train your aesthetic judgment in the field of contemporary art, decide for yourself if it’s important or valid, and discuss with others. Feel things and process those feelings, pay attention to them, because that’s how you curate your authentic self.