Art as a Mood, or How to Experience Presence?

Have you ever noticed that a work of art does not so much “communicate” a meaning to you as it changes the atmosphere around you? This is especially true of abstract art. It seems to create a field in which you are not so much interpreting its meaning as entering into a different mode of experiencing. And this, according to Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, is the very function of art.

We are used to thinking of art primarily as a carrier of meaning. The Enlightenment taught us to extract meaning from everything, since the most important task seemed to be to understand and explain. A painting must “say” something, a book must “teach” something, music must “express” an intention. But Gumbrecht invites us to look deeper: art matters not only for what it signifies, but for what it produces as presence — it affects our bodies, our emotions, our capacity to be in the world and to experience the world.

In his book Production of Presence, Gumbrecht argues that modern culture has focused too much on interpretation, on the deciphering of meanings. We look at a painting as if its main task were to hide a message for us to discover. But if the primary function of art were only to transmit meaning, then any painting could be replaced with a text explaining it. What, however, is the effect of the work’s actual presence in the same space with us? Or to put it differently: the meaning of a printed book and an e-book is the same, but what changes when, instead of staring at a screen, we hold a heavy volume in our hands, hear the rustle of its pages, sense the smell of new paper? How do we describe this surplus effect beyond meaning?

By limiting our relation to art only to the extraction of meaning, we lose something more fundamental — the fact that art arises next to us, touches us, becomes an event of presence.

Look at a sculpture. Of course, you can analyze it: style, epoch, symbolism. But first of all, the sculpture is. It occupies space next to you, and you next to it. It casts a shadow; you can feel the weight of the stone from which it was made; its surface reflects light and feels smooth to the touch. It affects us before any interpretation — through its materiality. This is an impact of body on body, presence on presence. And even more — it is an experience of being-in-the-world together.

Such an effect cannot be fully explained, because it lies beyond meaning. It is not a “message” but a sensation, a kind of resonance that we undergo on both a bodily and emotional level.

Stimmung: Art as Mood

A central concept introduced by Gumbrecht is Stimmung. The German word resists direct translation: it is at once “mood,” “attunement,” and “atmosphere.” Stimmung names the capacity of art to tune us, like a musical instrument, to a particular state of experiencing the world.

Imagine reading a novel not for its plot, but for the way it holds you in a particular Stimmung — of unease, of calm, of exaltation. Or listening to a symphony, and finding yourself immersed in a sense of time and space that cannot be put into words. This is Stimmung: art as a mode of attunement, in which the world becomes newly perceptible, as if the work has re-tuned us as instruments.

From this perspective, the role of art is not to deliver ready-made truths but to create the conditions for experience. Art reminds us that we are not only thinking beings but also sensuous ones. It returns us to the body and to perception. The artist does not so much “communicate” an idea as create a form in which Stimmung emerges. The spectator does not so much “read” meaning as allow themselves to be enveloped by this attunement. And it is in this that the genuine encounter with art takes place.

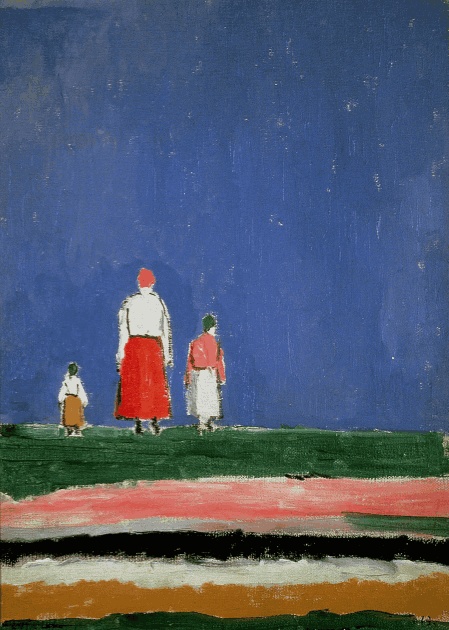

In everyday life we increasingly lose contact with the present. We process information, solve tasks, and perceive the world in fragments. Art brings us back to wholeness. It teaches us not only to know, but to be. Looking at Malevich’s paintings, we do not search for “meanings” but enter into a field of color that teaches us to experience something new. Art becomes an experience of presence in the world. And in it, we once again experience both ourselves and the world as something whole.

Ultimately, Gumbrecht shows that the task of art is not to explain, but to make us undergo something. A painting creates a space of experience in which we begin to feel ourselves: in contact with the world, in a Stimmung, in a new mode of being attuned.

And perhaps this is why art never grows obsolete. It does not simply tell stories (for every story has its expiry date!). Art produces presence. It opens the world to our experience, and our feelings become the primary and sufficient content of our psyche.

To describe this impact of art, Gumbrecht suggests using the term epiphany. An epiphany is a sudden moment of revelation, when a work ceases to be a bearer of meaning and becomes an event of presence. It is the moment when interpretation recedes, and art “speaks” directly through form, color, sound, or rhythm. Epiphany does not require explanation: it is felt bodily and emotionally, as an encounter with something greater than ourselves. Its force lies in allowing us to experience the world not through concepts, but through the intensity of presence — the presence of art and our meeting with it.